What Happens to the Irish Wolfhound Puppy with Portosystemic Shunt?

This article was published in Harp & Hound, Autumn 2018

Scarlett arrived August 2016, the second liver shunt puppy born into our family of hounds. She was fat, healthy and vigorous, giving no clue of the journey ahead. The following weeks were uneventful. She ate well, was vigorous with no neurological symptoms, but her growth wasn’t tracking with her littermates, and she began vomiting occasionally.

We met with an internist at North Carolina State. Bloodwork showed liver value changes, mild anemia and the bile acids were elevated. Her ultrasound showed a left-sided intrahepatic porto- systemic shunt, considered congenital and genetic in wolfhounds, caused by failure of the ductus venosus to close. The ductus venosus is a normal structure in the fetus, allowing the mother’s body to filter toxins for the fetus while its liver is developing. It begins closing within two to three days of birth, after umbilical cord circulation is disrupted. When the process fails to complete, it results in a type of shunt difficult to surgically correct.

Scarlett sleeping next to her brother, 2 ½ weeks

Scarlett’s options were limited, and the situation was grave. Her shunt wasn’t well placed, and her best option was transvenous coil embolization. This technique had been perfected by Chick Weisse VMD DACVS, currently at Animal Medical Center, NYC. It involves placing a stent in the caudal vena cava, which is recommended when close to adult body size due to concerns of the stent slipping out of position. This meant that we had to medical manage Scarlett’s shunt until she was between 10 to 12 months of age. Medically managing a giant breed is very different from a large breed or toy. I’m hoping this article will help others understand the complexities of treating portosystemic shunts and current therapies available.

Symptoms

Symptoms of liver disease are varied.

Neurological symptoms include lethargy, lack of coordination, disorientation, weakness, drooling, abnormal vocalization/crying, head pressing, problems with vision, pacing, unusual behavior changes such as aggression, circling, tremors, excitability, seizures, coma and collapse.

Gastrointestinal symptoms are vomiting, off colored stool, diarrhea or constipation, lack of appetite or a voracious appetite, or ingesting nonfood items including stool (pica). Dogs with intra-hepatic shunts are at increased risk for gastrointestinal ulcer- ation, which can lead to life-threatening complications if the ulcer begins to bleed or perforates.

Urogenital symptoms include increased thirst, urinary crystals or stones with subsequent urinary tract infections and enlarged kidneys. The puppy may have difficulty urinating and may need to urinate more frequently and with a larger volume than normal. High ammonia levels in the body can lead to ammonium urate stones.

Puppies with portosystemic shunts are often smaller, thinner and the coat may be of poor quality or unkempt. They may be prone to skin infections and can be itchy. They don’t tolerate anesthesia as well and are often slow to recover.

If the shunt is minor or partially closed you may not see any of these symptoms, so testing ALL puppies as late as possible and prior to going to their new homes is important. Even an apparently healthy puppy could potentially have a shunt.

Diagnosis

The primary screening for portosystemic shunt is through bile acid testing. There is conflict over the best time to screen, but most specialists in liver disease suggest later is better. Sharon Center DVM DACVIM, Cornell University, reported in Small Animal Pediatrics that Irish Wolfhounds can have delayed functional closure of the ductus venosus as late as 4 to 8 weeks of age, and recommends delaying screening until 16 weeks of age. Occasional false positives and negatives occur; false positives should be followed up with additional screening before making life-altering decisions. Additional diagnostics include the Protein C test, ultra- sound or CT scan to rule out a potential shunt. Companion owners should be educated on the potential for false negatives.

Bile Acids and Screening

The liver produces bile acids and stores them in the gallbladder. When a meal is eaten a message is sent to the gallbladder to contract and release bile acids into the duodenum (upper small intestine). The bile acids mix with food and assist in digestion and absorption of fats and fat-soluble vitamins. The bile acids are eventually absorbed into the bloodstream in the lower small intestine and returned to the liver, then collected and returned to the gallbladder and stored until the next meal. The bile acid test is performed by fasting the puppy for 12 hours and drawing a pre-fasting blood sample; the puppy is then fed a nutrient rich, easily digestible meal and a post-fasting sample is drawn 2 hours later. Both samples are evaluated, and the results show if the liver and small intestine are functioning correctly.

Bile acid testing is a screening tool and not a definitive diagnosis. An ultrasound or Computed Tomography (CT Scan) are warranted if results are elevated. Ultrasounds can be inconclusive, and the CT Scan is the gold standard, giving better information on size, complexity, location of the shunt and the best procedure for shunt closure.

Diet and Medical Management

A moderate protein diet is preferable, as adequate protein is critical for rapidly growing puppies. Muscle is the body’s second largest site for clearing ammonia through transient detoxification, good muscle tone gives the puppy an alternative for ammonia metabolism. Loss of muscle makes it harder to manage ammonia and puts the puppy at risk of Protein Calorie Malnutrition (PCM). If protein is heavily restricted it can lead to a negative nitrogen balance resulting in the puppy catabolizing muscle to meet its protein requirements; increasing the risk of Hepatic Encephalopathy (HE). It’s often assumed that the liver shunt puppy will be undersized and stunted, but with careful attention to diet, supplements and medications, this isn’t true in all cases.

Scarlett 5 months, ICU stay, bacterial translocation secondary to bacterial overload.

Ammonia can be lowered by choosing highly digestible protein sources which are low in purines. Plant based proteins are typically lower in purines, however unless properly combined they may not provide all essential amino acids when compared to meat sources. Good sources of low purine, highly digestible proteins, are low- fat yogurt, ricotta, cottage cheese, eggs and tofu. Nonessential amino acids in poorer quality protein sources may be subjected to increased breakdown by enzymes, resulting in greater ammonia production. Dairy and egg proteins have a high biologic value providing all essential amino acids and are highly digestible and absorbable. These amino acids are more highly utilized by the body and will produce less ammonia during metabolism. Providing the optimal ratio and amount of amino acids can assist in lowering the body’s amino acid burden. It is best to work with a Board Certified Veterinary Nutritionist to determine the optimal feeding plan for a growing puppy with a liver shunt.

The protein level should be as high as the puppy can tolerate without showing signs of HE or gastrointestinal ulcers. The National Research Council published nutritional recommen- dations for dogs of all life stages. They recommend a minimum of 45 grams of protein per 1,000 kcals of metabolizable energy with a recommended allowance of 56.3 grams of protein per 1,000 kcals of metabolizable energy. The protein level in the diet should meet or exceed the recommended allowance if the puppy is not showing signs of HE. The diet should have increased levels of branched chain amino acids, adequate arginine, avoid high sodium levels and include appropriate supplementation of vitamins and minerals. Carbohydrates should be highly digestible, good sources of fiber, and the main source of calories. The puppy should be fed multiple small meals a day, at least 3 and preferably 4, to reduce stress on the liver from ammonia and toxins. Lactulose should be split between all daily meals and can be poured on the food. A puppy with portosystemic shunt who feels GOOD will eat. If the puppy is refusing food, be watchful of gastrointestinal ulcers, or the potential for gastrointestinal perforation. Regularly assess body and coat condition, weight, muscle mass, behavior and activity levels.

Scarlett 5 months, ICU stay, bacterial translocation secondary to bacterial overload

Every puppy is unique and requires an individualized diet and different nutritional support, it isn’t a “one size fits all” illness. Some puppies tolerate higher levels of protein than others and protein intake should be maximized to a level the puppy can tolerate to support growth while avoiding PCM, controlling ammonia levels and reducing the risk of bacterial overload.

Aromatic Amino Acids, Branched-Chain Amino Acids And Hepatic Encephalopathy

Amino acids from proteins may be characterized as either Branched-Chain Amino Acids (BCAAs) or Aromatic Amino Acids (AAAs) and are provided by the diet. They assist in regulating metabolism, improve mood, regulate sleep, assist in carbohydrate metabolism, protein synthesis and assist in cardiovascular, renal and brain function. Shunts alter amino acid metabolism causing the amino acid profile to be off, reducing the ratio of BCAAs to AAAs (from 3-4:1 in healthy dogs to closer to 1:1 or less with shunts or chronic liver disease). The shunt puppy has higher AAAs and lower BCAAs, contributing to symptoms of HE. It’s been suggested in both veterinary and human medicine that supplementation with BCAAs could assist in normalizing the ratio between BCAAs and AAAs, although there is little documentation on the use of BCAAs in veterinary medicine. Human patients supplemented with BCAAs tend to have higher serum albumin levels and an overall better nutritional status and quality of life, although this may be a benefit of improved protein intake overall.

Scarlett, almost 4 months with PCM and muscle wasting due to too restrictive protein management.

Routine Preventitive Care

The puppy should be vaccinated as needed, but separating vaccines with guidance from your veterinarian may improve vaccination response and allow monitoring for adverse events. External and internal parasites should be treated and regular fecal analysis for parasites performed. Choosing appropriate products can be challenging and should be guided by your veterinarian.

Standard Medications

Lactulose is a synthetic non-absorbable sugar made from milk sugar lactose. It is metabolized by bacteria in the colon producing acids and trapping ammonia as ammonium. Ammonium is then removed from the body by defecation. Lactulose is given orally and should be given with each meal and to effect. It tastes sweet, dogs tolerate it well, viewing it as a treat. The dosage should be based on the consistency of the stools. Too much will cause diar- rhea; too little the stools will be too solid, stools should be soft but formed.

Antibiotics are given in maintenance dosages until the shunt is repaired. If the owner cannot afford to repair the shunt, antibiotics are continued for life to reduce bacterial levels and sepsis. Antibiotics reduce bacterial protein metabolism that contributes to the body’s ammonia burden. Antibiotics effective against ammonia producing bacteria (urease producers), such as neomycin or metronidazole are given. In some cases, broad- spectrum coverage is necessary and will be prescribed.

Sucralfate treats gastrointestinal hemorrhage and ulcers in the stomach and the duodenum. Ulcers are common with portosys- temic shunts. Sucralfate forms a gel when it encounters stomach acid, adhering to areas of inflammation or ulceration and acting as a protectant to the damaged area, allowing for healing and reducing the risk of perforation.

Omeprazole reduces the risk of gastrointestinal ulcers and hemorrhage. A puppy with an intrahepatic shunt should be placed on Omeprazole twice daily for life, even after shunt repair.

Anticonvulsants are started before the shunt is repaired. Seizures are a potential post-operative complication.

Useful Supplements to Consider

There are only limited clinical studies in veterinary medicine supporting their use, but significant documentation in human medicine. If you choose to use any of these please first consult with your veterinarian about including any of these supplements and their dosing.

Denamarin is a combination of Milk Thistle (active ingredient Silymarin) and SAM-e. Silymarin blocks toxins from entering the liver, assists in removing them and aids in the regeneration of liver cells. SAM-e is produced naturally in the body and is a precursor to glutathione.

Psyllium is a soluble fiber which can assist in lowering ammonia and works as a prebiotic encouraging the growth of short chain fatty acids.

L-Ornithine/L-Aspartate, L-Citrulline and L-Arginine have ammonia lowering properties and may be beneficial with portosystemic shunt.

Vitamin E and Selenium are antioxidants which protect the liver from further damage.

B Vitamins help with liver regeneration, mental acuity, coordination, prevent nerve damage and anemia.

N-Acetyl/L-Cysteine (NAC) is a building block of glutathione, a naturally occurring antioxidant.

Probiotics suppress the invasion and growth of pathogenic bacteria in the intestine.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids help protect the liver from inflammation and damage.

Zinc supplementation can reduce copper absorption.

Vitamin A and Copper should be restricted due to the risk of liver toxicity if too much is given.

Options for Closure of the Shunt

The goal of surgery is to attain complete closure gradually over an extended period to reduce the risk of seizures and portal vein hypertension. Intrahepatic portosystemic shunts are difficult to repair surgically, but if the surgeon can find an approach his first choice will likely be an ameroid constrictor or a hydraulic occluder. Alternative surgeries are full or partial closure of the vessel using silk suture or cellophane banding. The risk of complications with silk suture are greater than with the ameroid constrictor or hydraulic occluder. Cellophane banding works best with vessels under 3 mm; since most wolfhound shunts are larger, this method hasn’t been particularly successful in the U.S., though they have had success in the U.K.

The ameroid constrictor is a stainless-steel ring with a casein interior which is placed around the vessel and swells when in contact with fluids and slowly closes the shunt. The hydraulic occluder is made completely of silicone and has an exterior pump that can be used to pump fluid into the occluder to slowly close the shunt. This method gives the doctor more control over timing and can be reversed if portal vein pressure is too high.

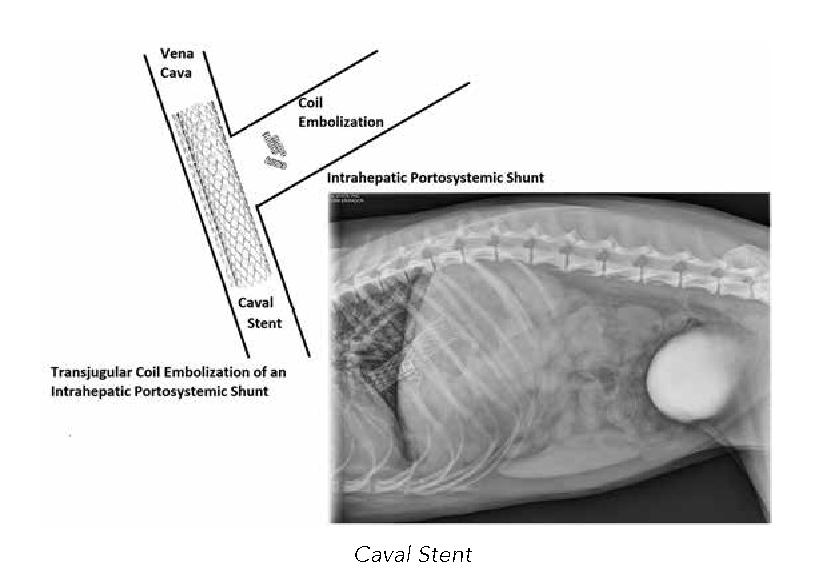

Caval Stent

Intrahepatic shunts often don’t lend themselves to surgical closure, making the only option percutaneous transvenous coil embolization. A mesh stent is placed in the caudal vena cava, and thrombogenic coils are dropped via guide wires and a catheter into the shunt. The stent acts as a “screen door” keeping the coils in place. The coils cause embolization of the vein over time, slowly closing the shunt. When the procedure is complete this is how it looks on x-ray. The complication risk is the same as other methods of closure, but with a reduced number. There is an added risk of coils migrating through the stent and into the lungs. The puppy needs to be near fully grown before the stent can be placed, as it may become displaced as the puppy grows.

If a method of closure is used which slowly closes the shunt over time, the outcome is good for most puppies. The success rates with ameroid constrictors, hydraulic occluders and percutaneous transvenous coil embolization is over 80 percent. When discussing options with the surgeon be sure to ask how many procedures have been done and try and find a surgeon who is experienced.

Life Expectancy

The health and quality of life improves with proper medical management and muscle development. There is some vari- ation in reporting average life expectancy with hounds only receiving medical management, but of those surviving the first year and successfully managed, 2 to 4 years appears to be the norm. Typical reasons for euthanasia are gastrointestinal ulcers/ perforation, seizures, portal hypertension or uncontrolled neurological symptoms. The best option is surgery if the hound has a single congenital portosystemic shunt. When surgery is successful the puppy can expect a similar life expectancy and quality of life as any other hound.

References

Sharon Center DVM DACVIM, “Nutritional Support for Dogs and Cats with Hepatobiliary Disease,” Small Animal Pediatrics: The First 12 Months of Life

Chick Weisse VMD, Allyson C. Berent DVM, Kimberly Todd, Jeffrey A. Solomon MD, Constantin Cope MD, “Endovascular evaluation and treatment of intrahepatic portosystemic shunts in dogs: 100 cases (2001–2011),” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 244(1):78-94 · January 2014

Eric Monnet DVM PhD FAHA DACVS DECVS, “Managing portosystemic shunts (Proceedings),” CVC in San Diego Proceedings, Oct 01, 2011

Karen M Tobias DVM MS DACVS, “PORTOSYSTEMIC SHUNTS,” vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/54.- Portosystemic-Shunts.pdf

Fryer KJ, Levine JM, Peycke LE, Thompson JA, Cohen ND, “Incidence of postoperative seizures with and without levetiracetam pretreatment in dogs undergoing portosystemic shunt attenuation,: Journal of Vet Internal Med, 2011

Kim SE, Giglio RF, Reese DJ, Reese SL, Bacon NJ, Ellison GW, “Comparison of computed tomographic angiography and ultraso- nography for the detection and characterization of portosystemic shunts in dogs,” Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound, 2013

Greenhalgh SN, Reeve JA, Johnstone T, Goodfellow MR, Dunning MD, O'Neill EJ, Hall EJ, Watson PJ, Jeffery ND, “Long-term survival and quality of life in dogs with clinical signs associated with a congenital portosystemic shunt after surgical or medical treatment,” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 2014

Cornelis HC Dejong, Marcel CG van de Poll, Peter B Soeters Rajiv Jalan, Steven WM Olde Damink, “Aromatic Amino Acid Metabolism during Liver Failure,” The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 137, Issue 6, 1 June 2007

Susan E. Johnson DVM MS DACVIM, “Update on hepatopro- tective therapies (Proceedings),” Nov 01, 2010, CVC in San Diego Proceedings

Chick Weisse VMD DACVS, “Interventional Radiology: A Trend in Veterinary Medicine,” Clinician’s Brief, October 2014

This article has been reviewed by Valery Scharf DVM MS DACVS, Clinical Assistant Professor, Small Animal Soft Tissue Surgery, North Carolina State University; Laura Gaylord DVM, Clinical Nutrition Resident, NCSU-CVM 2012-2016; and Michael Adams DVM.

Photos courtesy of Tamara Dunn

This page was last updated 01/04/2021.